This is the first of several posts taking a deep dive into the classic Soviet weightlifting text, Managing the Training of Weightlifters. This post looks at the first chapter of the book, which seeks to predict the future to drive today’s training and the second chapter, which looks at the press.

The first chapter deals with looking at the past to predict future results in weightlifting. This is done on two levels, first looking at where performance in each weightclass is going. This is important because we want our athletes to be competitive internationally so we have to know what we’re looking at in terms of potential competition. Second this is looking at an individual athlete’s performance, what’s a realistic improvement to shoot for, and how to program for that.

The authors begin by noting that weightlifting results are increasing. In a moment I’ll show an image of that from the book. They attribute this to two broad reasons. First, more people are participating in weightlifting worldwide (as of 1982). This increases the potential talent pool for the sport and this means better results. We could see this in the United States when CrossFit increased the pool of weightlifters in this country. Second, the authors feel that coaching and the science behind the coaching are both getting better.

As of 1982, weightlifters were training eight to ten times a week and two to three times a day. The authors don’t feel that it is realistic to increase this in order to increase performance because athletes have to recover. So how will athletes improve? The authors provide four things to look for:

- Qualitative execution of training loads. This means smarter planning of the training.

- Perfection of technique.

- New training influences.

- Better means of recuperation

In their analysis of results, the authors note that (understandably) achievements are best during Olympic years. World records tended to last three to four years for the lifts and four to five years for the total (I have an image showing this below).

In summary, the authors feel that this is an important tool to manage a weightlifter’s training. It sets out concrete aims and directs all the means and methods of training to the achievement of those aims.

Now, if you think about it this would also apply to sports like track and field, swimming, cycling, speed skating, etc. anything that is measurable.

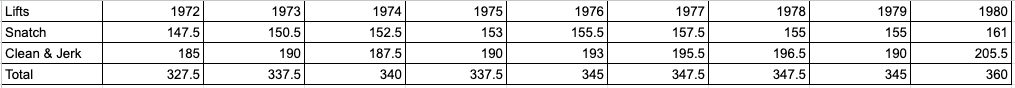

Below is an image looking at the best lifts from 1972-1980 in the 75 kilogram weight class. Note that these lifts are in kilograms.

Chapter two is a fascinating look at how eliminating the press changed weightlifting. When the book was published in the Ukraine in 1982 the press had been gone for only ten years! The authors spend a lot of time thinking about the impact on an athlete’s physique and training. At one point they complain that instead of strong and sturdy athletes they need those with physical preparation, mobility, long muscles, and that basically they were going to have to recruit track and field athletes.

The authors point out that the press used to be the most important exercise. Nobody was good at the snatch or clean and jerk (the so-called quick lifts), everyone was good at the press. In the past, 40% of training time was spent on the press. The authors lament the fact that the Soviet Union excelled at the press. Essentially, they feel that training athletes to be really strong (i.e the press) is really easy, but training for the quick lifts is a lot more difficult.

The authors note that with the press being eliminated, athletes won’t do less training it will just be redistributed to focus on the snatch and clean/jerk. This emphasis makes back and leg muscles more important than with the press. The authors worry that Olympic lifters will become all back and leg muscles.

Due to the technique with the snatch, clean, and jerk the authors feel that presses will have to be taken from 40% of training volume to around 10%. Not only that, the presses will have to focus on improving the snatch and jerk (so snatch grip push presses, jerk grip push presses, etc.) instead of the press. They also have recommendations for training volume distributions: Snatch 27%, clean and jerk 20%, presses 10%, squats 20%, pulls 15%, and other exercises 2%.

Laputin, N.P. and V.G. Oleshko. (1982). Managing the Training of Weightlifters. Zdorov’ya Publishers, Kiev. Translated by Charniga, Jr, A. Published by Sportivny Press, Livonia Michigan.